Inside the Deuterocanon: What Is the Apocrypha?

The Bible, so it would seem, is the definitive scripture of the Christian faith. Of course, little in religion is ever that simple. While we can agree that an anthology of books called “The Bible” constitutes the writings around which Christianity is based, exactly which books constitute the Bible is a matter of disagreement among the three major branches of the faith—namely among the Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant denominations.

Much of this disagreement concerns a series of writings that would appear to be part of the Old Testament. While the books that compose the Old Testament span over a millennium, some of these writings are conspicuously late in history—so far removed from their predecessors as to arouse suspicion among theologians.

Today, we know these books as the Apocrypha—from the Greek αποκρυπτεΐνη, or “hidden.” It is from the omission of these books that they have taken this name, a word that lives on in common parlance as “apocryphal” for disputable legends and myths. So, what is the Apocrypha, exactly, and what is all the argument and hiding all about?

Late Additions To the Septuagint

The tale of the Apocrypha begins in the time between the testaments—a period of roughly 400 years. It was during this time that Hellenistic Judaism emerged, fusing Jewish and Greek cultures together throughout the southern and eastern Mediterranean. As the Alexandrian Empire extended its influence east of Greece and Asia Minor and into what we know today as the Middle East, the Jewish diaspora from their homeland of Israel began in earnest, and Greek supplanted Hebrew as the common language of the Jewish people. This meant that Greek-speaking practicing Jews struggled to read the Torah and other religious writings, which remained in then-dormant Hebrew. Translation of these books was necessary. Just as King James would later convene a committee of translators to bring the Bible into English, Ptolemy II, descendant of Alexander the Great, asked seventy-two scholars to translate the Torah and the Hebrew Bible into Greek. This edition would be called the “Translation of the Seventy,” which would later take the Latinate name of “the Septuagint.”

Why Do Protestants Reject the Apocrypha?

The Septuagint would serve as a source material in translations of the Bible to Latin. As a Greek document, it would continue as the definitive form of the Old Testament for the Eastern Orthodox Church, which has remained firmly within a Greek sphere of influence to this day. It would not, however, be a primary source for the King James Bible. The Masoretic Text, what we consider the authoritative compendium of Old Testament books, was the translators’ choice, working straight from the original Hebrew rather than translating a translation. The scholars who compiled the Septuagint included more recent writings around which rabbinical Judaism had not formed a consensus. Because the Hebrew Bible did not include books such as Tobit, Judith, and the Wisdom of Solomon, nor did the King James Version. While Christianity has since diverged from Judaism in significant and self-evident ways, many Protestant churches affirm their connection to Judaism and respect it as a fellow Abrahamic faith. Protestant theologians have thus paid close attention to the rabbinical perspective on these books. The Jewish community does not regard these books as canonical, inspired word—and protestant denominations concur.

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church include this additional content and consider it just as divinely inspired as the rest of the Bible. Catholics, who accept these books as canonical, bristle at the term “Apocrypha” and its implication of lesser or disputed status. Instead, the Catholic Church regards these books as the Deuterocanon, or “second canon,” placing them on equal footing with the books of the Old and New Testaments that you will find in the traditional King James Version. Instead, Catholics limit the designation of “apocryphal” to books even obscurer to Protestant readers, such as books that the Eastern Orthodox Church includes as canonical but other churches do not.

The Council of Trent, the Catholic Church’s formal response to the events of the Protestant Reformation, established several key ecumenical positions as the Church reckoned with the rise of Protestantism throughout the traditionally Catholic lands of western Europe. Among these was the council’s 1546 declaration that the deuterocanonical books were equal to the rest of the canon. This dialogue between Catholics and Protestants would continue through the years. The Westminster Confession of Faith, the statement of the Church of England, declared “not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the canon of the Scripture, and therefore are of no authority in the church of God.”

The Books of the Apocrypha

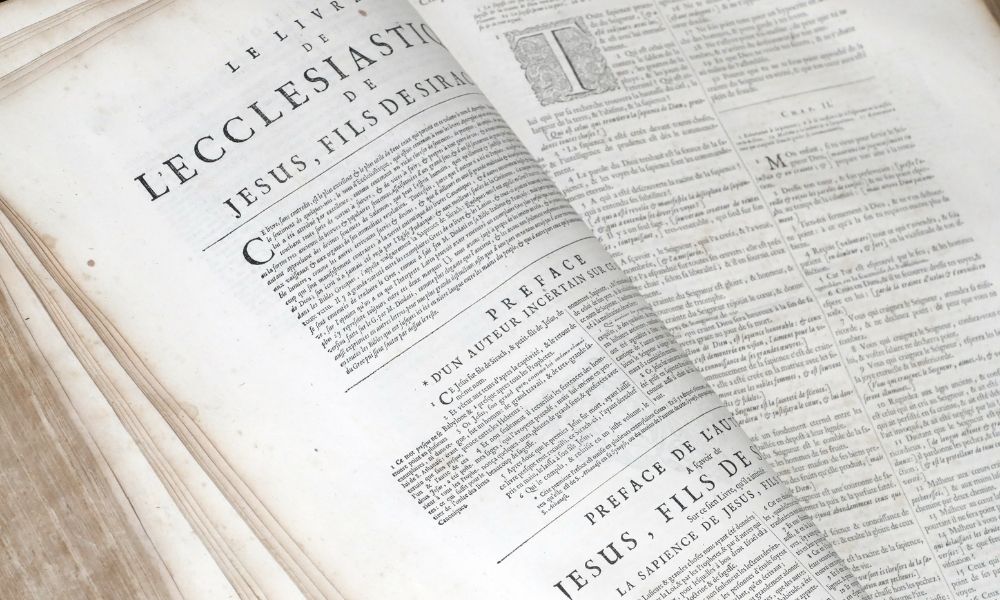

What Catholics regard as the second canon consists of the books of Tobit, Judith, Baruch, Sirach, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and the Wisdom of Solomon. The second canon also includes additions to the protocanonical books of Esther and Daniel, as well as further additions to the deuterocanonical book of Baruch. Orthodox Christians accept further books as canonical: the Prayer of Manasseh, 1 and 2 Esdras, Psalm 151, and 3 and 4 Maccabees. In the Orthodox Church, these books are the αναγεννησκόμεν, or anagignoskomena, meaning “the books which must also be read.”

It’s not simply a matter of Protestant-Catholic tensions that these books remain out of the Protestant canon—theologians have very good reasons for continuing to withhold the Apocrypha. The Old Testament and the New Testament are, to be sure, markedly different anthologies of books with different lessons and philosophies. However, these anthologies are not independent of each other. The citations and quotations of the Old Testament within the text of the New Testament link them together into a cohesive scripture for the Christian faith. This forms the basis of cross-referencing, one of the fundamentals of Bible study. Study Bibles identify these cross-references and direct the reader to follow themes across books and Testaments. Further exploring these concepts and references is one of the most effective ways to read the Bible.

Conspicuous by their absence in this reading of the New Testament, however, are quotations of the books of the Apocrypha in the New Testament. This important connective tissue, so to speak, is missing, which almost seems to orphan them. Without the books of the New Testament affirming the lessons of these books as they do others, they are in a precarious position: what is the Apocrypha and its place without cross-referencing?

The Apocrypha and the KJV

While the King James Version of the Bible does not consider the Apocrypha canonical, that doesn’t mean that it is wholly without merit. Many editions of the KJV will include these additional books between the Old and New Testaments, often as an overture to Catholics who are curious about exploring the KJV for the first time. At the KJV Store, we offer premium leather Bibles—with and without the Apocrypha—for our readers to enjoy.